For now, the bond market sees continued growth. The yield curve has 'inverted' (10 year yields less than 2-year yields) ahead of every recession in the past 40 years (arrows). The lag between inversion and the start of the next recession has been long: at least 8 months and in several instances as long as 2-3 years. On this basis, the current expansion will likely last into mid-2019 at a minimum. Enlarge any image by clicking on it.

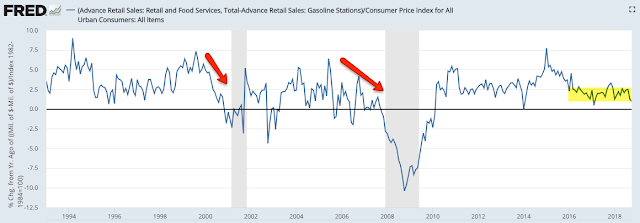

Likewise, real retail sales grew 2% and made a new all-time high (ATH) in October. The trend higher is strong, in comparison to the period prior to the past two recessions.

Housing is the primary concern. In the past 50 years, at least 11 months has lapsed between new home sales' expansion high (arrows) and the start of the next recession. So far, the cycle high was in November 2017, 12 months ago.

Unemployment claims have also been in a declining trend, but this may be changing. Historically, claims have started to rise at least 7 months ahead of the next recession: claims reached a 49 year low in mid-September, but have since risen the past two months. This measurement bears watching closely in the months ahead.

The Conference Board's Leading Economic Indicator (LEI) Index reached a new uptrend high in October. This index includes the indicators above plus equity prices, ISM new orders, manufacturing hours and consumer confidence. This index can fluctuate during an expansion but the final peak has been at least 7 months before the next recession in the past 50 years (from Doug Short).

Why does any of this matter for the stock market?

Equity prices typically fall ahead of the next recession, but the macro indictors highlighted above weaken even earlier and help distinguish a 10% correction from an oncoming bear market. On balance, these indicators are not hinting at an imminent recession; new home sales is the only potential warning flag (its most recent peak was 12 months ago) but it has the longest lead time to the next recession of all the indicators (a recent post on this is here).

Here are the main macro data headlines from the past month:

Employment: Monthly employment gains have averaged 207,000 so far in 2018, with annual growth of 1.7% yoy. Employment has been been driven by full-time jobs, which rose to a new all-time high in November.

Compensation: Compensation growth is on an improving trend. Hourly wage growth was 3.1% yoy in November, while the 3Q18 employment cost index grew 3.0% yoy, the highest growth in the past 10 years.

Demand: Real demand growth has been 2-3%. In October, real personal consumption growth was 2.9%. Real retail sales grew 2.0% yoy in October, making a new all-time high. 3Q18 GDP growth was 3.0%, the highest in 3 years.

Housing: Macro weakness is most apparent in housing. New home sales fell 12% yoy in October. Housing starts fell 3% yoy and permits fell 6% yoy in October. Multi-family units remain a drag on overall development.

Manufacturing: Core durable goods rose 2.9% yoy in October. The manufacturing component of industrial production grew 3.0% yoy in October, to the highest level in 10 years.

Inflation: The core inflation rate remains near the Fed's 2% target.

This is germane to equity markets in that macro growth drives corporate revenue, profit expansion and valuation levels. The simple fact is that equity bear markets almost always take place within the context of an economic decline. Since the end of World War II, there have been 10 bear markets, only 2 of which have occurred outside of an economic recession (read further here).

When the economy is expanding, the historical risk of a 10% annual decline in the stock market is just 4% (from Goldman Sachs).

The highly misleading saying that "the stock market is not the economy" is true on a day to day or even month to month basis, but over time these two move together. When they diverge, it is normally a function of emotion, whether measured in valuation premiums/discounts or sentiment extremes.

We had expected macro data to be better than expected in 2H18, but it hasn't been. Macro data was ahead of expectations to start the current year by the greatest extent in 6 years. During the current expansion, that has led to underperformance of macro data relative to expectations into mid-year and then outperformance in the second half of the year (green arrows). 2009 and 2016 had the opposite pattern: these years began with macro data outperforming expectations into mid-year and then underperforming in the second half (red arrows). This is another watch out for 2019.

A valuable post on using macro data to improve trend following investment strategies can be found here.

While the macro data is fine, a possible wild card is the escalation in trade war rhetoric, which reduces global demand, raises prices and eventually leads to lower investment (from St Louis Fed).

While the macro data is fine, a possible wild card is the escalation in trade war rhetoric, which reduces global demand, raises prices and eventually leads to lower investment (from St Louis Fed).

* * *

Let's review the most recent data, focusing on four macro categories: labor market, end-demand, housing, and inflation.

Employment and Wages

The November non-farm payroll was 155,000 new employees less 12,000 in net revisions for the prior two months.

Employment growth had been decelerating. The average monthly gain in employment was 240,000 in 2015, 211,000 in 2016 and 190,000 in 2017. In the past 11 months, however, the monthly average has improved to 207,000 (green line). If this holds until year end, it will be the fourth best year for employment since 2000.

Monthly NFP prints are volatile. Since the 1990s, NFP prints near 300,000 have been followed by ones near or under 100,000. That has been a pattern during every bull market; NFP was negative at times during 1993, 1995, 1996 and 1997. The low print of 34,000 in May 2016 and 14,000 in September 2017 fit the historical pattern. This is normal, not unusual or unexpected.

Why is there so much volatility? Leave aside the data collection, seasonal adjustment and weather issues; appreciate that a "beat" or a "miss" of 120,000 workers in a monthly NFP report is within the 90% confidence interval (explained here).

For this reason, it's better to look at the trend; in November, trend employment growth was 1.7% yoy. Until spring 2016, annual growth had been over 2%, the highest since the 1990s. Ahead of a recession, employment growth normally falls (arrows). Continued deceleration in employment growth continues to be an important watch out.

The labor force participation rate (the percentage of the population over 16 that is either working or looking for work) has stabilized over the past 5 years. The participation rate had been falling since 2001 as baby boomers retire, exactly as participation started to rise in the mid-1960s as this demographic group entered the workforce. Another driver is women, whose participation rate increased from about 30% in the 1950s to a peak of 60% in 1999, and younger adults staying in school (and thus out of the work force) longer.

A better measure is the prime working age (25 to 54 year olds) labor force participation rate; it stands at 82.4%, down only slightly from its peak in 2000 at 84%, and much higher than anytime prior to the 1980s.

Average hourly earnings growth was 3.1% yoy in November, the highest in 9-1/2 years. This is a positive trend, showing demand for more workers. Sustained acceleration in wages would be a big positive for consumption and investment that would further fuel employment.

Similarly, 3Q18 employment cost index shows total compensation growth was 3.0% yoy, the highest in the past 10 years.

For those who doubt the accuracy of the BLS employment data, federal individual income tax receipts have also been rising to new highs (red line), a sign of better employment and wages (from Yardeni).

Demand

Regardless of which data is used, real demand has been growing at about 2-3%, equal to about 4-5% nominal.

Real (inflation adjusted) GDP growth through 3Q18 was 3.0% yoy, the best growth rate in 3 years. 2.5-5% was common during prior expansionary periods prior to 2006.

Stripping out the changes in GDP due to inventory produces "real final sales". This is a better measure of consumption growth than total GDP. In 3Q18, this grew 2.9% yoy. A sustained break above 3% would be noteworthy.

The "real personal consumption expenditures" component of GDP (defined), which accounts for about 70% of GDP, grew 3.0% yoy in 3Q18. This is approaching the 3-5% that was common in prior expansionary periods after 1980 and prior to the great recession.

On a monthly basis, the growth in real personal consumption expenditures grew 2.9% yoy in October.

GDP measures the total expenditures in the economy. An alternative measure is GDI (gross domestic income), which measures the total income in the economy. Since every expenditure produces income, these are equivalent measurements of the economy. Some research suggests that GDI might be more accurate than GDP (here).

Real GDI growth in 3Q18 was 2.6% yoy.

Real retail sales grew 2.0% yoy in October and made a new ATH. Sales fell yoy more than a year ahead of the last recession.

Retail sales in the past three years have been strongly affected by the large fall and rebound in the price of gasoline. In October, real retail sales at gasoline stations grew by 13% yoy after having fallen more than 20% yoy during 2016. Real retail sales excluding gas stations grew 1.0% in October.

This expansionary cycle is not like others in the past 50 years. Households' savings rate typically falls as the expansion progresses; this time, savings has risen and remains at an elevated level.

Core durable goods orders (excluding military, so that it measures consumption, and transportation, which is highly volatile) rose 2.9% yoy (nominal) in October. Weakness in durable goods has not been a useful predictor of broader economic weakness in the past (arrows).

Industrial production (real manufacturing, mining and utility output) growth was 4.1% yoy in October. The more important manufacturing component (excluding mining and oil/gas extraction; red line) rose 3.0% yoy. Both are at a 10 year high. Industrial production is a volatile series, with negative annual growth during parts of 2014 and 2016.

Importantly, nearly 80% of industrial production groups are expanding. A drop below 40% will imply widespread weakness that typically precedes a recession (from Tim Duy).

Weakness in total industrial production in 2015-16 was concentrated in the mining sector, with the worst annual fall in more than 40 years. It is not unusual for this part of industrial production to plummet outside of recessions. With the recovery in oil/gas extraction, mining rose 13% yoy in September.

Companies are often wrongly accused of underinvesting in lieu of greater share repurchases (buybacks). But capacity utilization is still under 80%, so there is plenty of room for production to expand within existing capacity.

Housing

Macro weakness is most apparent in housing. New housing sales fell 12% yoy in October after reaching their highest level in 10 years in November 2017. Housing starts and permits fell 3% and 6%, respectively, in October, with weakness in multi-family units the most pronounced. Overall levels of construction and sales are small relative to prior bull markets.

First, new single family houses sold was 544,000 in October; sales in November 2017 were the highest of the past 10 years. Growth in October was -12% over the past year after rising +13% yoy in October 2017. YTD, new home sales are tracking +3% growth over 2017.

Second, housing starts fell 3% yoy in October. Starts in January were at the highest level of the past 11 years. The cycle high print has typically been well over a year before the next recession (arrows).

Single family housing starts (blue line) reached a new post-recession high in November 2017 but were 8% lower in October. Meanwhile. multi-unit housing starts (red line) has been flat over the past four years; this has been a drag on overall starts.

Inflation

Despite steady employment, demand and housing growth, core inflation remains near the Fed's target of 2%.

CPI (blue line) was 2.5% last month. The more important core CPI (excluding volatile food and energy; red line) grew 2.2%. Core CPI was at current levels between January 2016 and February 2017 before falling back below 2%. CPI growth has fallen in the past 4 months; inflation was near a low a year ago (arrow), meaning the yoy growth is likely to moderate in the months ahead, all else being equal.

The Fed prefers to use personal consumption expenditures (PCE) to measure inflation; total and core PCE were 2.0% and 1.8% yoy, respectively, last month.

Some mistrust CPI and PCE. MIT publishes an independent price index (called the billion prices index; yellow line). It has tracked both CPI (blue line) and PCE closely.

Summary

On balance, the major macro data so far suggest continued positive, but modest, growth. This is consistent with corporate sales growth. SPX sales growth in 2018 is expected to be about 6% (nominal).

With the rise in earnings and the drop in share price, valuations are now below their 25 year average. The consensus expects earnings to grow about 10% in 2019. Even if this falls to just 5%, equity appreciation next year can be driven by both corporate growth as well as valuation expansion (chart from JPM).

If you find this post to be valuable, consider visiting a few of our sponsors who have offers that might be relevant to you.